In a career spanning over 30 years working with over 120 different franchise brands, I’ve been around long enough to see high growth, market-leading, and high potential franchise brands squander their market opportunities and stagnate or fail despite recent past success.

Apparently, this “snatching failure from the clutches of success” phenomenon is commonplace in business. I once heard famed business author Jim Collins give a presentation about his follow-up book to the bestseller Good to Great. Several years after the release of this book, Collins was often criticized because the stock performance of 11 of the companies he declared “great” underperformed in the S&P 500. Furthermore, some “great” companies like Circuit City filed Chapter 11, and Fannie Mae was delisted by the New York Stock Exchange. Collins studied the dynamic of how success breeds failure and published his findings in his follow- up book, How the Mighty Fall.

Collins saw a 5-stage linear progression of common mistakes successful company leadership made after they achieved success. For greater readability, I altered the names of some of the stages but kept their meaning intact:

Stage 1: Excessive pride

Stage 2: Undisciplined and irresponsible pursuit of more

Stage 3: Denial of risk

Stage 4: Decline in results

Stage 5: Turnaround or acceptance of brand irrelevance or failure

The first three stages start as leadership character flaws which manifest as “the truth,” (“We really ARE smartest guys in the room!”). These attitudes eventually become ingrained in the company’s leadership culture and management philosophy, which in turn impact decision-making, strategy, goal-setting, risk tolerance, and resource allocation. This creates strategic overreaching (ie: new product or service extensions, brand acquisitions, taking on ill-advised debt) and tactical misfires, ultimately translating into an unexpected decline in results.

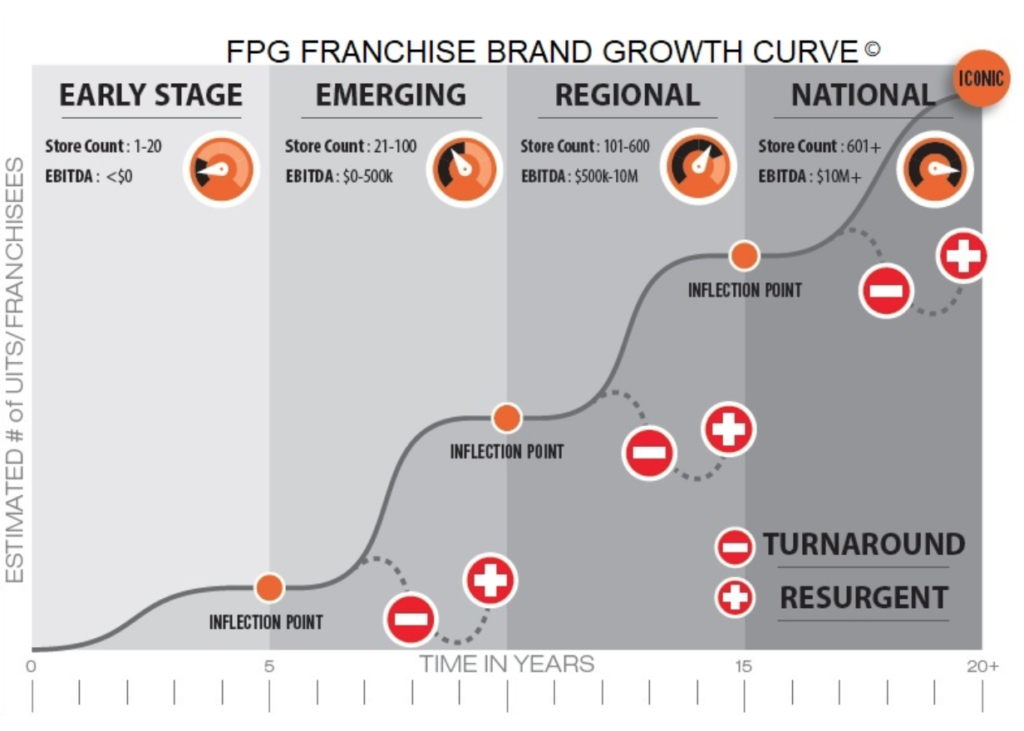

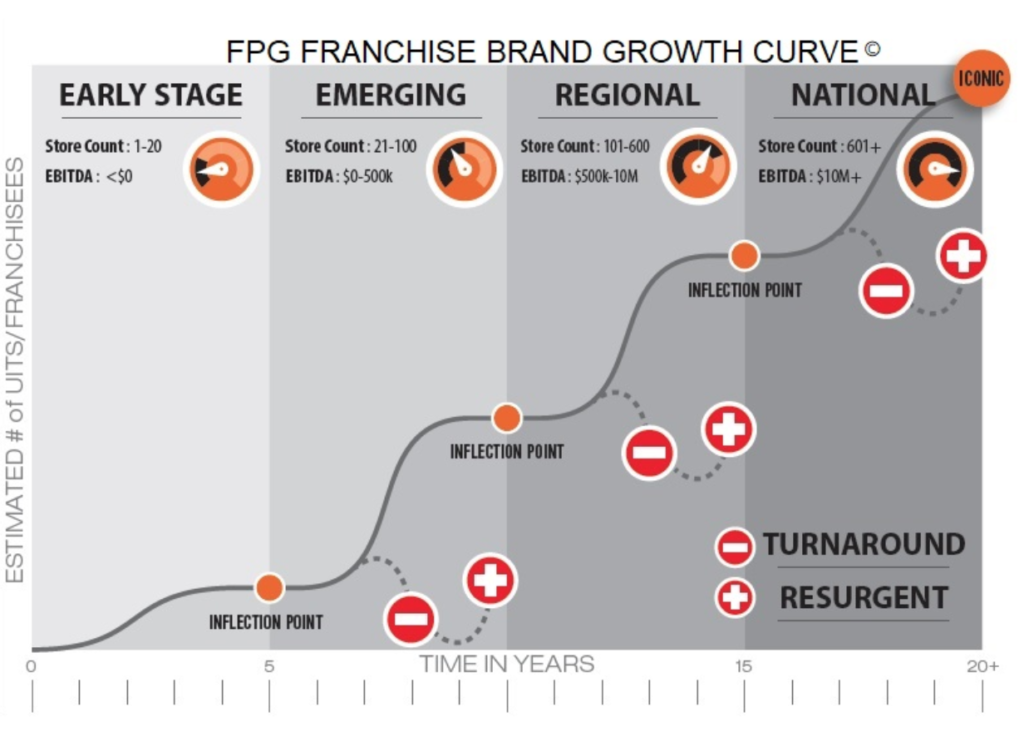

While Collins developed this model by studying big business, over the years Franchise Performance Group (FPG) has witnessed a franchising corollary, leading us to develop a model we call the FPG Franchise Brand Growth Curve, which we discussed in detail in a blog titled Franchisor Life Cycles.

FPG asserts that large national and iconic franchise brands become so by successfully passing through a series of stages: Early Stage, Emerging Growth, Regional, and National. A few choice national brands, such as McDonalds, go on to weave themselves inextricably into the American culture. See the model below.

Each stage brings its own unique set of challenges that the franchisor must overcome before progressing to the next stage. On top of the strategic challenges we document in the article, franchisors are also susceptible to the same kind of self-deception, self-limitation, and self-sabotaging as those companies depicted in How the Mighty Fall.

For instance, a study by research firm Franchise Grade revealed that after four years, 30% of startup franchises had one or zero franchise locations. In 2017, FranData published a report that showed 61% of the approximately 3,800 franchise brands had fewer than 25 operating locations, territories, or units, and 82% had fewer than 100. FPG franchisor financial models show a typical franchisor will not cross the threshold of royalty self-sufficiency, meaning the franchisor can sustain operations without needing franchise fee revenue, until they have 40-100 operating units or franchisees. FPG believes royalty self-sufficiency is a key indicator of a franchisor’s resiliency and sustainability. Therefore as many as 80% of the current crop of franchisors carry significant brand risk. Assuming no franchisor enters franchising with the intention of multiplying their risk with little or no return to show for it, how could thousands of companies so dramatically overestimate the franchise investor demand for their concepts?

Stage 1: Excessive pride is often first visible when the brand ownership first decides to franchise. Brand ownership has some success as an operator and develops a success system which at least proves itself on a small scale with one or perhaps a handful of units to create financial benefit for the ownership. The brand’s ownership jumps into franchising, assuming a built-in market exists for their business opportunity without understanding the required investment, risk, resources, skills, and time necessary to successfully launch a franchise brand or which type of franchisees they should focus on recruiting. The often see franchising as a lead generation and franchise sales problem. Seemingly through the power of positive thinking, they believe the market will reward their unrefined brand with its incomplete and unproven business system with a windfall of franchisee investment dollars.

Often they reject or see little value in investing in experts, vendors, and experienced executives who have successfully developed tools, processes, systems, campaigns, tactics and strategies leading to the growth of profitable regional and national brands on their watch. Instead, brand ownership establishes a DIY mentality, completely contradicting the pitch they offer franchise candidates about the wisdom of working with experienced industry professionals and unnecessary added risk of going it alone.

Excessive pride is also visible in how some franchisors approach the franchisee-franchisor relationship. Often franchisors become overly dictatorial, controlling, and possessive. They think, “my brand, my customers, my systems.” They consider franchisees almost as indentured servants of the brand who exist to drive the franchisor’s revenues, profitability, and enterprise value. These attitudes ultimately manifest as an us-versus-them culture, where franchisees’ risks, investments, and efforts are not valued by the franchisor. This creates infighting and negative validation that kills franchise candidate interest and leads to stagnant or declining unit counts as franchisees become more frustrated and either close or exit.

Stage 2: Undisciplined pursuit of more is visible during most stages of the growth curve. This happens when the franchisor consumes itself more with how to find the next franchisee than how to help existing franchisees become more profitable and expansion-ready. The “pursuit of more” shows a lack of understanding of how franchising really works. The “pursuit of more” brand leadership doesn’t seem to ask the important questions such as: “What did we accomplish on behalf of our existing franchisees to deserve more new franchisees?” and “Can our system absorb more new growth while improving on the ramp-up time and current KPIs?” and the most telling of all questions, “Why are we pursuing candidates? Why don’t franchise candidates pursue us?”

“Pursuit of more” franchisors often assume there is more available market to grab without examining their assumptions and calculating the downstream impact on the brand such as existing personnel, (“Do they have the skills and capacity to handle more responsibility?”) market demand (“How do we know there is a greater market to pursue?” and “Where is this new projected interest coming from?”) and brand value (“How do we increase the value of our business model to attract more quality franchisees?”).

“Pursuit of more” and “excessive pride” franchisors believe they are market anomalies who won’t follow the normal critical path franchisors need to take to build a valuable brand. Most high-growth systems achieve exponential growth and expansion as a natural byproduct of creating a learning culture that embraces continual refinement, leading to consistently improving franchisees’ profitability and more accelerated new unit ramp-ups. As a result of organizational skills, effort, and applied institutional learning, each year new units and territories open with stronger and more accelerated KPIs than in previous years. Results are coming easier, faster, cheaper, and more consistently than in previous years (more consistently is underlined because smart brands find a way to eliminate operator error, results fluctuations, and financial risk through better training, processes, and operating systems). As a result, existing franchisees have high confidence and keep expanding, and new franchise candidates become intrigued with the brand’s success and feel compelled to learn the brand story. These brands are pursued by smart franchise candidates. FPG calls this phenomenon “pull demand,” while “pursuit of more” is what we consider “push demand.” FPG explains the transformation from “push demand” to “pull demand” in our article titled The Franchise Flywheel Effect.

In over 30 years of franchising, I find all unique, profitable, defensible, and high-value franchise brands eventually create pull demand. “Push demand” franchisors’ leadership consistently misinterprets low brand value, leading to low brand demand as a franchise sales problem rather than a brand worthiness problem.

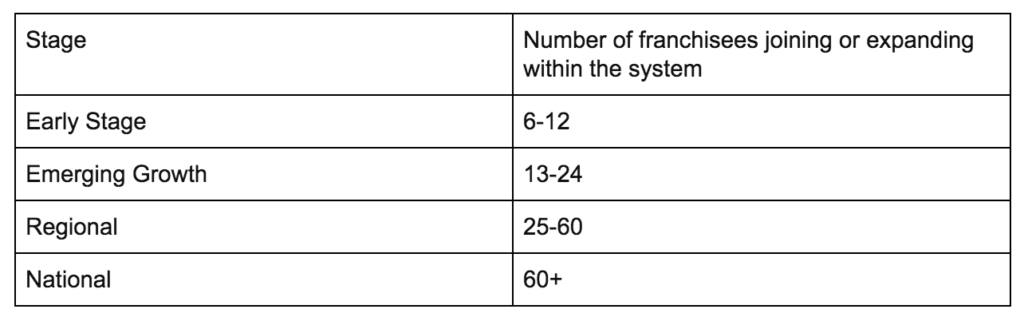

Most of the successful franchisors that FPG works with track the new unit growth numbers depicted in the following chart:

The reward for successfully navigating each stage should be improved ramp-ups, better unit-level economics, and greater pull demand.

Stage 3: Denial of risk. This occurs when the franchisor’s leadership assumes they are ready for the next wave of exponential growth without doing the critical thinking, analysis, training and developing of personnel, and making the necessary investments to scale their business properly or to solidify their base of existing franchisees. They may overestimate their organizational capabilities or ignore market conditions such as entering new markets with strong local or regional copycat concepts that don’t exist in core markets. They may believe the brand has key strategic advantages like good customer service and quality products, as if these attributes are unique to their brand instead of a simple baseline customer expectation and a requirement of doing business within the category. For example, when I ask food franchisors “Why should a franchise candidate invest in your chain?” I often hear, “We have good food.” My follow-up is always, “So what? You are a restaurant chain; you are supposed to have good food. Why else should someone invest in your chain?”

Often these brands that are just meeting baseline expectations get copied and improved upon by smart copycat concepts, making new markets difficult to develop and commoditizing the product and service offering, which dilutes the value of the brand. This helps usher in Stage 4: Decline.

Keep in mind these decisions that lead to eventual decline are made when all indicators show the brand is winning. The impact of these decisions — stagnation and decline — often occur 2 or 3 years after key strategic decisions are made, making it difficult for leadership to trace results back to these decisions, adding additional brand risk and making a Stage 5: Turnaround more difficult.