Why 8 out of 10 franchisors peak before they are sustainable and how to avoid their costly mistakes.

By Joe Mathews

Founder, Franchise Performance Group (FPG)

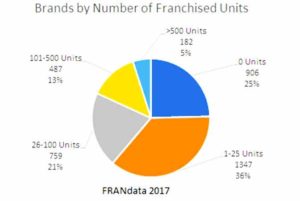

Talk to any number of franchise brands at the IFA Convention with fewer than 100 franchisees or locations, and a troubling theme will emerge: An alarming number of franchisors have not been able to grow, mature, and strengthen their brand as they expected. Some have halted growth altogether; others have declined from peak numbers, weakening the franchisor’s financial position and eroding customer and investor confidence, perpetuating the negative spiral and making a turnaround more difficult. Even more troubling are the large numbers that have ceased operations. Research firm FRANdata recently reported 82% of existing brands have less than 100 units or locations. In 2017, the distribution looked something like this:

FRANdata reported at the start of 2017 there were approximately 3,800 franchisors in the United States. In any given year, approximately 250-350 new brands elect to franchise. However, FRANdata and FPG also estimate that in any given year, only 13,000 to 20,000 new franchisees enter the market. That’s stiff competition for very few buyers.

In typical markets where supply exceeds demand, the classic case of oversaturation, prices go down and margins get squeezed until enough brands exit, allowing the surviving brands to create a sustainable level of profitability. In the current franchisor climate, however, franchise fees have escalated and new franchisors continue to enter the market, creating a state of disequilibrium. Franchisors are either ignorant of the hypercompetitive market or simply overestimate the investor demand for their business. But, as always, market forces will drive disruptive change, creating winners and losers along the way.

FPG franchisor financial models show that typical brands don’t achieve royalty self-sufficiency until they pass the 40- to 100-unit mark, and according to one presenter at a recent IFA conference, fewer than 5% of franchisors reach 100 units within a 10-year time frame. Since most franchisors don’t have 10 years of financial staying power, they find themselves selling franchises to anyone who will buy them, just to survive. Franchisors focus on short-term cash needs and strategy goes out the window. Clearly, this is not a recipe for success.

In 1998, business school professor Scott Shane studied the problem and published his results in an article titled MIT Sloan Management Review. He researched 157 companies in 27 industries that became franchisors between 1981 and 1983. He looked at their progress after 12 years. He was surprised to learn 75% of his sample group ceased to exist.

The franchisors who break the 100-unit barrier follow a predictable path that looks something like this:

Early Stage franchisors

In what FPG labels “Early Stage,” quality franchisors start as successful local concepts, typically with fewer than 20 operating units, locations or territories. While they may have demonstrated proof of concept for their corporate operating business model, they struggle with establishing proof of concept as a franchisor. Better capitalized and more sophisticated franchise buyers already know about the high failure rate for both Early Stage franchisors and pioneering franchisees, and therefore sit on the sidelines and watch.

According to FRANdata, Early Stage franchisors represent approximately 60% of franchisors in the U.S. marketplace. According to the data, it would appear only one-third successfully graduate from Early Stage to Emerging Brand status.

Where many Early Stage franchisors fail

In my 30+ years of franchising, I’ve seen more franchisors fail to actualize their potential not because of competitive threats, but because of how they view their own business. Early Stage franchisors often view their business from an insulated insider’s perspective, rather than looking at the business from a more classic supply-and-demand, industry and franchise candidate/investor perspective.

For instance, they say to themselves, “I did well. I put my kids through college and built wealth and cash flow. I’m no Harvard MBA or Zuckerberg wunderkind, but I believe I can teach anyone to do what I do.” Coming to to the table with an “If I did it, then anyone can do it” perspective, they automatically assume their business could and should be a franchise. They enter franchising with unrealistic expectations and completely underestimate the time, money, effort, complexity and sophistication it takes to build a profitable and sustainable franchise brand.

Simply put, Early Stage franchisors often suffer from self-delusion, assuming that since their concept plays well in small venues, they’re naturally ready for a national stage.

Franchising is stacked with franchise attorneys and franchise consultants who count on this to easily convince business owners their business is “highly franchiseable” and perhaps “the next big thing” and then charging professional fees of $150,000 or more to “package a franchise for sale” and “impart the Winning Formula.”

Early Stage franchisors more often than not fall into one or more of the following predictable traps:

- They come out too early. Their brand is underdeveloped and their processes and systems are unrefined, leading to inconsistent, unpredictable and unacceptable franchisee results. While the systems may work well for ownership and company managers, they may not be granular enough for new entrepreneurs who have no experience in the industry. These system flaws extend the franchisees’ learning curve, burning precious cash. Additionally, the brand may look and feel small and local, which doesn’t translate well into a national platform.

- They overestimate the demand for their franchise. The fish don’t jump in the boat as planned or promised by the professionals who set them up as a franchisor. Remember, FRANdata estimates less than 20,000 people per year invest in a new franchise.

- They underestimate the amount of time it takes to get established. Several years in, they feel like they’re running in quicksand, questioning what happened. Remember, one recent study showed less than 5% of franchisors get to 100 units or territories in less than 10 years.

- They are undercapitalized. They were told it takes $150,000-$250,000 to get started, but later find out they need to invest $1 million-$2 million before they achieve royalty self-sufficiency and organizational stability. They simply operate cash-strapped, contradicting what they tell franchisees they need to look like to succeed.

- They reject sound, practical advice from professionals. They believe they know better. On one hand, they espouse to franchise candidates the value of experience and the risk of doing it all yourself. On the other hand, they reject investing in real world franchising experience, choosing to go it alone.

- They recruit anyone who will buy their franchise. They don’t critically think through what it takes to be successful pioneering franchisees, don’t have the discipline to walk away from underqualified candidates, or simply grab the cash because they are undercapitalized.

- Leadership wears too many hats. They operate as a part-time franchisor and part-time unit-level operator, leaving no time to do either particularly well. Key employees often don’t have mastery-level expertise in the multiple tasks they’re responsible for.

- Their marketing and brand may be too unrefined. The brand promise may be too vague or confusing to attract new customers in new markets and, by default, new franchise candidates.

- New market penetration strategy may be undeveloped and ineffective. Franchisor may have not mastered their complete revenue model, lacking systems, operations, marketing and support to simultaneously increase and optimize customers’ dollars-per-transaction, customer frequency and customer retention.

- The business may be behind the technology curve. The business may not be fully leveraging the latest and best technology effectively for their customer-facing and franchisor-related business systems.

Emerging brands

If a franchisor is successful at recruiting, training, developing and leading a small team of 20 or so profitable franchisees, the franchisor graduates from Early Stage into Emerging Growth Franchisor status.

Smart, capitalized and aggressive franchise candidates target such brands for investment. In the world of the more sophisticated player, the thought process is, “I don’t want to be a pioneer. They get arrows in the back. I don’t want the franchisor to experiment with my time and money.” They equate the Early Stage with “unmitigated risk.” In their world, once a franchisor has it all figured out (which often means 20 or more units, territories and locations), they have a tendency to step up and cherry-pick the most lucrative markets.

Once a franchisor successfully navigates through Early Stage, they will start feeling momentum. In the Early Stage, it feels like the franchisor is pushing a boulder up a hill. In the Emerging Growth Stage, it feels like the boulder has crested the hill and is now starting to roll down the hill on its own power, which introduces a whole new set of operational issues.

While a franchisor may have mastered what it takes to successfully onboard up to six franchisees per year, they are suddenly faced with a new problem: How do we successfully onboard 12-30 new franchisees per year?

Growth fuels brand awareness, driving year-over-year revenues to historical highs. Added units provide the franchisor with greater purchasing power, driving costs down and creating more resilience and liquidity. Growth also helps the franchisor build its brand as the employer of choice, adding more responsible and talented workers on both the franchisee and franchisor levels. The franchisor continues to refine its model, shortening the time to break-even, value-engineering the investment level down, negotiating better financing programs for startups and expansions. Simply put, everything appears to be working better all at the same time.

It’s right about this time that franchisors begin to believe they now possess what it takes to build a large national brand. The reality is that they have only enough steam to carry them to the next growth stage. As the graph shows, they will eventually experience decreasing marginal returns as they approach the stage. At this point, successful brands reinvent their organization again to capitalize on the opportunities presented to successful regional brands. We will address how brands successfully graduate from Emerging Growth to Regional brands at a later date.

Where many Emerging Growth franchisors Fail

- Overstretched operations and support. Franchisors don’t design their support systems to scale. New franchisees received highly personalized attention and support in the Early Stage. Franchisors don’t staff to provide the next wave of franchisees with the same level of support, often elongating new franchisee ramp-up and hurting unit-level economics. Staff often pull double-duty, taking on roles within the organization beyond their pay grade or in areas where they have little experience.

- Undercapitalization. Franchisors may take 10 years to graduate from Early Stage to Emerging and cannot staff up as necessary. They wait for added royalty and franchise fee revenue, staffing as cash allows rather than as growth demands. Cash-strapped franchisors can’t fund necessary initiatives or fix systems buckling under the pressure of growth. They postpone certain fixes, hoping problems don’t escalate and become unfixable downstream. The franchisor has difficulty securing expansion capital for themselves and may resist taking on private equity or expensive mezzanine financing.

- The Peter Principle. Famed management consultant Laurence Peter observed that employees and managers are promoted based on their performance in their current role, rather than how well they are suited for their intended role. As franchisors struggle to stay organized, employees are often promoted past their point of competence, leading to downstream organizational breakdowns.

- Brand disconnects. As the brand continues to grow, new and existing customers raise their level of expectations. They demand a more polished brand, efficient systems and a more unified and cohesive customer experience. This means greater investments from both the franchisor and franchisees, often before they have reaped a strong return on existing investments.

- Leadership. Franchisors often have highly personal and informal interpersonal relationships with franchisees in the Early Stage. As the chain accelerates, leadership creates more professional boundaries, such as not taking a franchisee’s call on a Sunday afternoon. Early Stage franchisees begin to experience how growth is changing their relationship, and often they don’t like it. Many decide to exit at this stage, thinking, “The culture changed. This isn’t the system I bought into.”

- Corporate culture. Struggling to keep up with growth, franchisors begin hiring leaders and employees from other franchise chains. Because the role demands that employees and leaders build the plane while they’re flying it, they never learn or acclimate to the franchisor’s culture. Instead, they solve problems, manage and lead they way they did in their previous corporate culture or cultures. This often creates a breakdown with franchisees and with valued existing employees, creating franchisee dissatisfaction and franchisor turnover, at a time when the brand is counting on its experienced employees to step up and take on more.

- Lack of communication. In over 30 years of franchising, I have never heard a franchisor or franchisees of a rapidly growing Emerging Growth franchisor say, “You know what our problem is? We over communicate!” Franchisors run at 100 miles per hour, often not knowing what each other is doing. This lack of communication can create franchisee and employee relationship fractures and isolated work silos.

- Supply lines. Some vendors may be having a hard time keeping up. Other vendors start raising their prices, thinking it is an opportune time to start reaping the benefit of your success. Some suppliers may have a hard time getting products to new markets, putting a burden on new market franchisees.

- Lack of systemic thinking. Franchisors get caught up in a one-off “break-fix” mentality, spending most of their time and energy fixing one problem at a time rather than studying how the overall system created a series of individual breakdowns. Franchisors work on the franchisees’ symptoms but ignore the systemic breakdowns that created the symptoms in the first place. Often they blame their problems on poor franchisee attitudes and execution before they look at the quality and scalability of their systems or skills and experience of their employees.

- Marketing. Franchisors begin to move from community marketing tactics to advertising co-ops in some markets, requiring a different level of marketing sophistication and greater coordination among franchisees. Franchisors may pull the trigger on additional marketing co-op fees guaranteed to them under the terms of the franchise agreement. Franchisees may push back, not seeing the value.

- Increased competition. Copycat concepts start emerging, threatening the franchisors value proposition in existing markets and making it more difficult and costly to enter new markets. They watch the market and design business which appear fix the problems which hamper the market leaders.

- The Founder’s Trap. It takes the personality, initiative and drive of a founder/CEO to power a franchisor past Early Stage into Emerging Growth Stage where the chain gathers momentum. It’s toward the end of the Early Stage where the sheer force of personality no longer works. The founder needs to elevate to CEO and build an organization that drives results. The micromanaging that worked in the Early Stage becomes a barrier to continued growth in Emerging Stage. If the founder can’t elevate from a “run and gun” entrepreneur into a CEO who manages through objectives, strategies and tactics and runs a quality organization, then the franchisor will begin burning out its valued employees and have difficulty attracting new talent. The market will only give the organization what the organization has the will and skills to handle. Additionally, many entrepreneurs start business because they don’t function well inside of corporate environments. As the chain grows, these entrepreneurs find themselves having to create the same corporate structures they swore they’d never be part of again. This “I must become what I despise” mentality creates organizational stress, resistance and conflict.

The data suggests about half of Emerging Brands crack the code, find their way past 100 units or territories and graduate to Regional Brand status.

In future blogs we will dig into where Regional and National brands get off track and become Turnaround brands.

What successful brands have in common

Successful franchisors understand they are in two separate and distinct businesses:

- The customer-facing business

- The business of franchising

FPG defines the business of franchising as “Recruiting, training, developing, financing, resourcing and leading a team of profitable franchisees.” Ultimately, we see franchising as a two-metric business: Strong, consistent and predictable unit-level economics paired with trusting and workable franchisee-franchisor relationships. Many franchisors see franchise sales as the linchpin to success. We see franchise sales and development results as a natural byproduct of how franchisees are performing financially and how franchisees are embraced among the franchisor’s leadership and employees.

For example, how hard would it be to recruit franchisees for a franchisor with a highly profitable model, great long-term growth potential and who collaborates with franchisees, treating them with dignity and respect? If you first resolve the franchisee profitability issues and rebuild trusting relationships, at the same time you will also be resolving franchise sales problems. Strong operations drive strong franchise development results. In the face of weak operations or breakdowns in the franchisee-franchisor relationship, franchise sales results will be the first to suffer and the last to come back during a turnaround.

We’ve received perhaps a hundred calls from franchisors wanting to fix their development problems without touching operations. They think, “Yes, we have issues with operations, but we need to sell what we have.” But the franchise buyer doesn’t need your operations problems. They have choices. The market rewards strong operations with consistent and predictable returns, just like the stock market.

The most common mistake franchisors make

- They don’t do what it takes master both businesses.

- They don’t understand where they are in the growth cycle.

- They don’t know what it takes to graduate to the next stage.

About FPG

If you have operations, marketing and unit-level mastery, we bring franchising mastery. Consider FPG as a franchisor without a franchise brand. Our clients bring a solid, well-branded and well-executed business model that has already successfully moved beyond the Early Stage to Emerging Growth. FPG brings the intellectual property, skills, executive experience, strategic relationships and capital necessary to scale your operation and grow a national brand. Our combined value equation looks something like this:

If you need and value the experience of franchise expansion market leaders, we should talk.

Joe Mathews, CEO Franchise Performance Group

Joe@FranchisePerformanceGroup.com

860.309.1484