By Franchise Performance Group’s CEO and Founder, Joe Mathews.

Ultimately, franchising is a two-metric business. The first metric is unit-level economics. Are franchisees’ financial returns meeting their expectations? The second metric is the quality of the franchisor-franchisee working relationships. How would franchisees rate the takeaway value of the franchisors’ training, support, and performance management systems? Would franchisees say the value of the tools and support they receive is greater than or equal to the royalty dollars invested? Do franchisees, employees, and leadership of the franchisor trust each other and work towards crafting mutually profitable campaigns, offers, and solutions? Do franchisees feel they are heard and understood? Does information routinely flow up and down the organization or just funnel down from on high? Would franchisees say they are informed about issues important to them? Would they say they feel like an integral part of a team or more like the low man on the totem pole?

The way franchisees would answer these questions speaks volumes about the organization’s corporate culture. While strong financial returns go a long way to resolve franchisee-franchisor relationship strain, financial performance does not substitute for trusting and workable franchisee-franchisor relationships. Iconic national franchise brands offer franchisees both.

Franchisors with a strong, inclusive, collaborative, franchisee-friendly corporate culture will attract more sophisticated and talented franchise candidates than more heavy-handed franchisors who resort to threats, punishment, and coercive command-and-control techniques to try to keep franchisees in line.

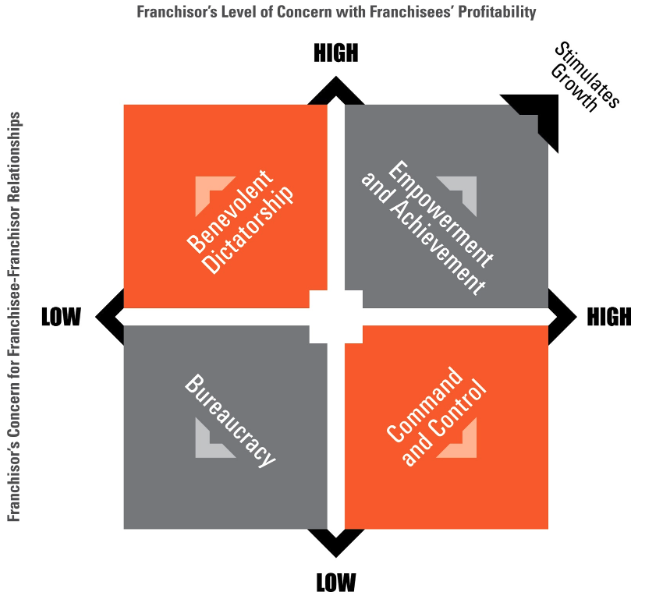

Dr. Jay Hall, Ph.D., founder of Teleometrics, spent a lifetime studying the impact of corporate culture on individual performance. Dr. Hall has identified four prevailing corporate cultures, which FPG has modified to reflect what occurs in franchising. Each culture is marked by two distinguishing characteristics: the franchisor’s demonstrated level of concern for franchisees’ results and their concern for maintaining positive franchisee relationships.

Keep in mind that at any time, any company can exhibit traits from any one of the four cultures we will describe. But over the long haul, franchise organizations tend to exhibit dominant and consistent patterns of beliefs and behaviors, for better or worse, that franchisees and employees can predict and count on.

We will look at these cultures in a progression starting with the least effective and most likely to fail to the most effective and most likely to produce outstanding results for franchisees, shareholders, employees of the franchisor, and suppliers.

The Bureaucracy

Bureaucracies are highly legalistic, highly layered companies where the lower you go in an organization, the less decision-making responsibility and authority an employee has. The organization seemingly exists to maintain the status quo, avoid accepting personal responsibility, and elude being held accountable for producing results. When a franchisee is faced with a unique challenge or makes a special request, the knee-jerk reaction throughout the layers of management is “No,” coupled with “We don’t do it that way,” regardless of whether or not what the organization is currently doing actually works or remains in the franchisees’ or customers’ best interests. Change is met with stiff resistance, and individual initiative is frowned upon. Employees and franchisees are expected to follow the rules and resist original thinking. Policies and procedures are set to control employees’ actions, minimize the potential for mistakes, and ensure franchisee compliance, even at the expense of results.

Impact on Employees of the Franchisor and Franchisees

Consider the type of corporate employees and leadership that would survive in this corporate culture in the long-term. Those franchisor leaders and employees who are dedicated, results-oriented, efficient, entrepreneurial, visionary, big-picture thinkers, or out to make their mark in the world would be ostracized, and then quit or be fired. Only those who simply want to earn a steady paycheck while hiding out and avoiding personal responsibility would want to stick around for the long haul in this environment.

Because bureaucracies value sameness and security over performance and efficiency, they remain a breeding ground for institutional thinking and systemic underperformance.

Now think about the quality of the interactions between the bureaucratic franchisor support staff and the franchisees under their charge. Would these conversations and communications pertain more to tactics and strategies about how to drive franchisees’ sales and results, or would they tend more toward what franchisees must do to continually stay in compliance and avoid default letters?

Impact on Results

Franchising was invented to create a strategic advantage over the competition by flattening and decentralizing the brand, and increasing nimbleness by completely empowering trusted entrepreneurs charged with satisfying the customer. As you can see, bureaucracies are designed to create the opposite effect, destroying the key strategic advantage franchisors have over highly centralized chains. Therefore, bureaucratic franchisors have little staying power in today’s competitive commercial marketplace because they kill off what works. This is why most surviving bureaucracies primarily exist in the public sector where a free market does not exist, new competition is highly regulated, and customers have limited supplier choices.

Bureaucracy is not limited to large organizations. Bureaucratic thinking and behaviors can exist in companies of any size.

Benevolent Dictatorship

Benevolent Dictatorships are typically informal, folksy, low-stress companies where much attention is paid to making franchisor employees and franchisees feel welcome and wanted. Feeling good, being appreciated, and loyalty to leadership are often more important than bottom-line results. This culture is commonly found in small, startup, emerging-growth, family-owned, privately-held franchisors where the founder or owner places friends, family, and loyal underlings in key management positions.

Additionally, the demands of smaller, emerging-growth brands often require employees to wear multiple hats and work longer hours. Leadership values that kind of loyalty.

Existing franchisor employees are often not the most qualified people for their jobs, but they can be trusted to do ownership’s bidding without question or pushback. Unless an employee possesses the right last name, marries into the family, plays golf with the ownership, or has a long history of responding to the bidding of leadership without questioning them, there is little room for advancement. This corporate culture, left unchecked, is not designed or positioned to create a powerhouse national brand and will eventually be hamstrung by too many employees in positions where they are not effective.

These franchisors often don’t offer franchisees strategic support such as succession planning, professional development, getting expansion ready, risk mitigation, sales and lead generation, or how to best deploy capital. The franchisor often is set up to offer simple break-fix advice to less technically experienced or astute franchisees.

In a Benevolent Dictatorship, information and resources flow from the top of the organization downward to franchisees. Franchisee contributions aren’t valued, as the franchisor believes they know better than franchisees, or are psychologically threatened by the opinions and advice of franchisees. Business information and collaborative efforts initiated by franchisees seldom impacts the decision-making of the franchisor.

Impact on Employees and Franchisees

Because leadership or ownership has little faith in the capabilities of managers, staff, and franchisees, or surrounded themselves with a low-capacity but loyal team, power, money, and authority are concentrated at the top. Benevolent Dictator leadership often possess a mastery-level understanding of their model and are set up to offer insights, opinions, and helpful hints, but are not often set up as learning organizations designed to accelerate franchisees to also become technical masters.

Additionally, front-line franchisee support act as buffers and have no real decision-making or budgetary authority. Franchisees will diminish and bypass them, preferring to solve every problem by going right to the top rather than fiddling in the middle.

This creates two long-term problems that threaten the brand. First, the benevolent dictator’s front-line leadership will get marginalized and neutered by both brand ownership and the franchisees. Because middle management is relegated to the role of town squire to announce decisions to the citizens of the franchising fiefdom, they lose any future ability to lead. This means as the brand grows and the system demands more, they will rapidly diminish in overall effectiveness. They simply aren’t, and won’t be in the future, viewed either by franchisor ownership or franchisees as significant players.

Secondly, because front-line leadership is consistently bypassed, the franchisor’s ownership will wallow in the trenches of one-off problem-solving either on an employee or franchisee level, knocking them completely off their strategic plan and focusing on the key initiatives that can create organizational breakthroughs which uniformly elevate both franchisees and the brand.

Impact on Franchisees and Employees

Think of what happens to talented and upwardly mobile employees or franchisees of this kind of organization. The brand ownership calls the shots. Those who want to see their own ideas implemented, wish to collaborate in the decision-making process, or are unwilling to consistently do the bidding of the Benevolent Dictator brand ownership will not remain. They will find a culture that values performance, professionalism, and initiative.

Those who survive, play the game, and don’t rock the boat will often stay forever. As long as they can consistently produce on a minimally acceptance performance level, do the leadership’s bidding, and don’t show too much originality or initiative, they will find a home.

This means franchisees are supported by long-term employees who are motivated by peace and quiet and low drama. These employees strive to achieve minimally acceptable performance, meaning just enough to not get fired but not enough to raise expectations. They are geniuses of mediocrity.

Now watch the vicious circle that forms. You start to see that group behavior is always designed to perpetuate the existing group behavior. The existing culture is always designed to survive intact.

High performers and upwardly mobile franchisor managers will get frustrated and leave because their initiative gets squashed in middle management and isn’t valued at the top. They will jump ship and join a company that offers and values results, upward mobility, and professional development. That leaves the bottom-feeding loyalists as the go-to employees, perpetuating a culture of mediocrity.

Impact on Results

Now think about the quality of training and ongoing support these low-skilled officers and employees can offer franchisees. When franchisees first buy into a franchise, they will see high value in the franchisor’s training and support. As franchisees mature, they often outpace the franchisors ability to add more value and are left to their own resources. If franchisees complain about low value they receive for their royalties, they are often met with the response, “Don’t these unappreciative franchisees know how hard we work? Don’t they realize we are just trying to help them?” In such a scenario, intentions and appreciation are more important than performance and results.

These franchisees’ names are often added to a franchisee validation blacklist, which the franchise sales department uses to try to shield new franchise candidates from speaking with them.

This culture can work in lower entry cost and entry-level, owner-operator businesses where the owner is a technician, like hardwood floor restoration, gutter cleaning, junk removal, and carpet cleaning.

In 3-5 years, as franchisees mature and achieve the same or greater expertise level as the franchisor, top franchisees will typically silo, break off, and do their own thing. The franchisor has no more to offer them, but they find themselves still paying the lion’s share of the company’s royalty revenue. Many go negative, knowing their royalty streams go to prop up underperforming or new franchisees rather than get reinvested helping peak performers achieve the next level of results.

Command and Control

If I had to pick what I believe to be the most common corporate culture in franchising, it would be Command and Control. Command and Control companies have strong central authorities where most decisions are made. While power and authority may be more diffused than in the Benevolent Dictatorship culture, it’s still consolidated at the top. Data routinely flows up from franchisees to the corporate office, but decisions are more often than not handed down from the top. While franchisors may have advisory committees consisting of franchisees, these committees aren’t decision-making bodies. They exist to advise the decision-makers who are free to accept all, some, or none of the advice. In addition, franchisor leadership isn’t always transparent with information, disclosing only what they deem franchisees need to know. Information that would suggest a problem is either not shared or politically spun in a positive light.

While the franchisor leadership may verbalize such things as “franchisees are partners and stakeholders in the company,” their attitudes, actions, and contracts tell a different story.

Command and Control franchisors value compliance. However, today’s consumers value personalization and uniqueness, creating the potential for a material customer-to-brand disconnect.

Impact on Employees and Franchisees

Command and Control cultures are formed from several limiting and somewhat dysfunctional beliefs about the nature of people and how business is conducted.

These organizations are a byproduct of systematizing and institutionalizing fears, human frailties and leadership character flaws. Stop on that sentence and read it again. Let it sink in.

These fears, frailties, and character flaws are as follows:

- Over-possessiveness. “It’s my brand, my customers, my system, my advertising, my products and services.” Franchisees participate with the franchisor’s permission and under their jurisdiction.

- Low trust. “Franchisees can’t be trusted to follow the system. We need to constantly stay on top of them. They are always trying to get away with something.”

- Fear of loss of control. Consider franchisees enemies of the brand with competing interests rather than allies with aligned interests. “We can’t give franchisees too much power and control because they will abuse it.”

- Organizational self-centeredness. The employees’ goals are less important than the owner’s and leadership’s goals. The organizations tactics and strategies are to enrich ownership rather than to drive franchisees’ profitability and market share.

- Low value placed on franchisees’ contributions. Franchisor ownership and leadership want to build their brand using franchisees’ time, energy, and money. They see franchising as a faster, easier, and cheaper model to build their brand. In this perceived model, franchisors don’t see the franchisee community as a strategic advantage in the marketplace. They are a necessary cog in the brand wheel.

This culture eventually will strangle new unit growth and create heightened franchisee dissatisfaction. Left unabated, franchisees and the franchisor may go to war.

Impact on Results

Often, the franchisor has a blind spot, driven as much by a desire for power, control, and minimization of mistakes as they are driven by what they publicly profess as their core values. When asked why they want to start a business, aside from their financial objectives, franchise candidates almost uniformly declare they are seeking their version of wanting more power and control over their lives, careers, and investments. So you can clearly see why in this culture, where the franchisor seeks control and franchisees avoid being controlled, franchisee-franchisor conflict is inevitable.

That’s why companies with this dominant culture are so often sued by disgruntled franchisees, or routinely have franchisees banding together to create alliances to beef up their numbers to take a stand against the franchisor. It’s as if franchisees and the franchisor are designing a company where each fights the other for perceived control rather than the competition for market share.

Empowerment and Achievement

The Achievement culture creates the most fertile ground for cultivating an iconic franchise brand by providing an inviting work environment that attracts and retains highly skilled and self-directed franchise candidates, executives, and employees.

Franchisor leaders see their jobs as facilitators. They routinely interact with the top-producing employees and franchisee thought-leaders, making sure they have what they need to win. They identify and eliminate potential barriers to forward momentum. They are not egocentric or controlling. They give the necessary power, authority, and resources to those responsible for driving results. They are transparent with information. They are clear about the individual needs of employees and franchisees and work to align their individual goals with business objectives so everyone wins.

They have a bigger view than the Dictatorship or Command and Control viewpoint of “It’s my brand.” They would understand that the brand is community property and if the chain is to become iconic, the employees of the franchisor, franchisees, suppliers, and customers must each add value, receive value, and build relationships with the brand on their own terms.

When I ask franchise executives if they know what franchisees were looking to accomplish for themselves and their families when they invested in their franchise, more often than not, I hear “No.” It’s my experience that the typical franchisor doesn’t know whether or not its franchisees are winning according to the franchisees’ definition of winning. But strong franchisors do.

Empowerment and Achievement franchisor executives would see brand success as being a symphony of employees, franchisees, suppliers, and customers. They know if they get it right, the music will take on a sustainable life of its own and stakeholders will benefit in ways no one can predict.

Such companies are so unique and add value to so many stakeholders on every level that people often line up to do business with them. Qualified franchise candidates fill their franchise sales pipelines. Suppliers outbid each other for their business. Even highly skilled professional managers may take a pay cut or a step down on the org chart to get in. Seemingly, customers are waiting in the wings in new markets waiting for the opportunity to do business with franchisees.

Impact on Employees and Franchisees

Achievement cultures attract and retain top franchisor executives and employees and franchisee talent. Leaders, employees, and franchisees thrive personally and professionally within the teamwork-driven, results-oriented culture, unlocking the best of who they are and actualizing much of what they can achieve. The franchisor and franchisees experience being valued and respected. Suppliers feel like key strategic partners. They aren’t squeezed for every penny and at the same time expected to be at the franchisor’s beck and call. Employees of the franchisor are rewarded in a way that’s consistent with their performance, and they’re promoted based on merit. Because these cultures are most often found in high growth companies, growth opportunities exist.

Empowerment and Achievement cultures attract talent, building the franchisors brand as employer of choice. Franchisors seem to effortlessly find and retain highly skilled and dedicated franchise candidates and leaders, providing the best opportunity to amass the necessary talent pool to scale the organization and build a sustainable, iconic brand.

Franchisees and the franchisor enjoy rock-solid relationships. Both seem to understand that each needs to make a healthy return on their time and money and neither can perform at high levels unless their companies are healthy and profitable. When faced with a problem, they engage in win-win problem solving rather than win-lose fighting and arm-wrestling for control.

Franchisors don’t worry about franchisee recruitment. Existing franchisees represent at least 50% of new unit or new territory growth. New franchise candidates consistently throw their hat in the ring as a result of brand reputation.

Ownership and leadership believe they are operating from an Empowerment and Achievement culture because that’s what they espouse. But if you were to poll your franchisees, vendors, and employees, what would they say it’s like to work with the franchisor? Are they empowered or frustrated? Motivated or stifled? Do you trust their feedback or do they not have the freedom to answer the questions honestly? Do they say in the boardroom what they are saying in the bathroom?

Creating a Culture Shift

Remember, corporate culture is always designed to maintain the dominant group behavior and existing culture. That is why corporate culture transformation ALMOST NEVER OCCURS without outside help. Several times over the last few years FPG has been called on by executives to “fix” their people because “They’ve got the wrong attitude.” The executives, however, position themselves outside the culture and therefore outside the problem, which of course is the problem. Corporate culture begins at the top and filters down through the organization.

Corporate culture seems to follow Newton’s first law of motion, which states bodies in motion continue on the path unless interfered with by an outside force. Culture transformation requires interference by parties who are not already making up the existing culture. And corporate cultural transformation is a specialty few management consultants understand or have the skills to execute. It takes the patience of Job, the acceptance of Christ, and the long-suffering and peaceful willpower of Mahatma Gandhi and Mother Teresa. Culture shifts don’t happen immediately and smoothly. It’s a rocky road. Culture experts agree that these attitudinal and behavioral shifts take at least three years to be habitually adopted through every level of the organization.

But here is the good news. Once a franchisor accomplishes an organizational shift into an Empowerment and Achievement culture, the new culture will staunchly police and protect itself. The new culture’s resistance to change will ultimately work in the franchisor’s favor and move the brand towards a new breakthrough or tipping point.

Successful Evolution of Culture

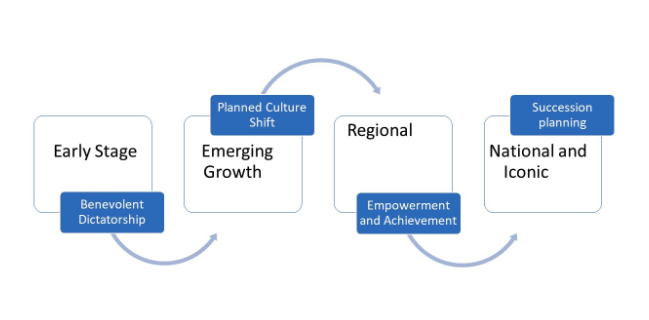

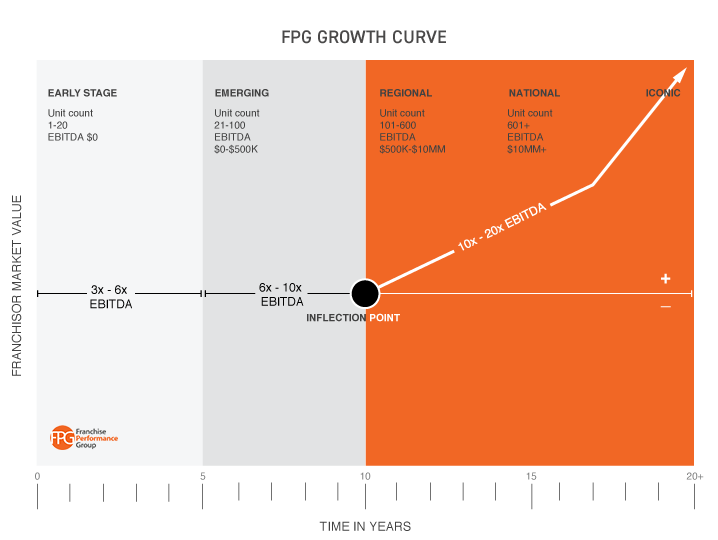

A franchisor operating in the United States evolves and moves along the life cycle below. The corporate culture also evolves as the chain matures.

Unless the franchisor is already a significant chain that enters franchising later in their life cycle, most franchisors enter Early Stage and Emerging Growth as Benevolent Dictatorships. These companies are generally privately held and tightly controlled where leaders and front-line franchisee support wear multiple hats and perform functions they were never adequately trained for.

Early on, franchisees are treated like family. Leaders develop close interpersonal relationships. The brand maintains this family-style relationship until growth stretches the companies and the folksy “call my cell phone day or night whenever you need me” is no longer workable. As the brand grows and the organization begins to hire professional management and domain-area experts like marketing, training, real estate, and field support, Early Stage franchisees no longer have immediate access to the franchisor’s leadership. Professional boundaries form.

The business evolves from a highly decentralized and flat organization where no one says, “It’s not my job” to an organization with clear job descriptions, clear personal, departmental, and organizational objectives. The franchisees will experience a shift from an informal culture where everyone knows your name to a more professionally run organization with formal boundaries.

Smart franchisors anticipate this shift and manage franchisees’ expectations upfront and often. Franchisees join such franchisors because they want to participate in the Early Stage of a successful brand and have easy access to decision-makers. Early Stage franchisees see themselves as brand pioneers, playing a meaningful role in a brand’s long-term success. They trade off immediate access to ownership for mature and refined business systems. They desire a pivotal role in helping the franchisor battle-test systems and help the brand establish a beachhead in new markets.

But they generally do not know in advance what changes to expect as the chain expands. Smart franchisors spend extra time communicating to their Early Stage and Emerging Stage franchisees exactly what to expect over time and what growth and change will mean to them and the franchisee-franchisor relationship. By securing franchisees buy-in, the franchisor has the freedom to naturally grow and evolve without staunch franchisee resistance.

Smart franchisors don’t hire staff out of need. They also have accurately assessed who the organization’s “high potentials” are and either hired outside mentors or budgeted time and resources to tee them up for success in their next role.

They also know for which positions they will need to bring in outside talent. To avoid requiring all new employees to fix the plane while they are flying it, they make the investment and build their organization 6 to 12 months in advance. This allows the brand to educate the new hires on how to effectively work inside of an Empowerment and Achievement culture, minimizing the risk of having new hires import and embed dysfunctional organizational behaviors from previous cultures.

When done right, the culture will experience a natural ebb-and-flow maturity process that will look something like this:

De-Evolution of Culture

As stated, most Early Stage and Emerging Growth franchisees are treated like the franchisor’s family. This continues until growth makes this culture no longer workable.

Most nuclear family relationships appear to be defined by two major characteristics: love and dysfunction. When working well, franchisee and franchisor relationships transcend business and each take a vested interest in the other’s success. As culture breaks down, if not managed properly in advance, franchisee-franchisor engagement can degrade into antagonistic, hypercritical, and sometimes vicious encounters.

These relationship breakdowns occur as chains experience success and begin the move from the Emerging to Regional stage. If growth and relationships are being managed properly, the chain will evolve into an Empowerment and Achievement culture. When managed incorrectly, franchisors’ leadership may react to franchisee pushback by creating a legalistic and authoritarian Command and Control structure.

As chains grow, the increasing demands outstrip many of the franchisor’s team members’ ability to keep pace. On-the-job training worked when growth was a trickle. However, as the chain enters exponential growth, the franchisor should be hiring experienced high-capacity executives whose leadership capacity exceeds the franchisor’s rate of growth. But that’s often not what happens.

Benevolent Dictators value loyalty. Sometimes they are loyal to a fault. They give their team many opportunities to step up and perform, seemingly blind to the notion that demands exceed their team’s capacity to deliver. Meanwhile the system continues to break down and relationships fracture. The franchisor’s team has the experience of being like the little Dutch boy running around sticking fingers in the holes of the dike, but unable to address the systemic and organizational problems that created the fractures in the first place.

Because franchisees stop getting the attention they’ve been used to, they start doing their own thing, often inconsistent with brand identity and brand standards, creating brand disconnects and confusion in the mind of the customer.

Poorly managed growth creates a franchisor experience of spinning out of control. The franchisor spends all of their day in a break-fix mentality, resolving one-off conflicts and issues and completely knocked off their strategic plan. Work stops being fun.

The franchisor knows their team is spread thin. Sometimes valued employees buckle under the pressure and quit, and the chain loses precious brand and technical expertise at the time they need it most. The franchisor begins to hire out of desperate need, onboarding managers and leaders from other chains. These new hires embed processes, procedures, and organizational behaviors from past chains. The franchisor begins to look and operate like a patchwork quilt of stop-gap solutions imported from other brands. Because new hires are expected to build the plane while they are flying it, they often don’t have the time to stop and assess or align their approach with brand identity and brand values.

Eventually, franchisor leadership gets fed up with their loss of control and franchisee-franchisor friction and starts tightening the screws on the franchisee community. By doing so, they usher in a new era of Command and Control.

This culture doesn’t work in franchising. Franchising works through influence, mutual respect, and alignment of franchisee and franchisor interests. Entrepreneurs by their very nature resist strong-arm tactics. As franchisors make this shift, they will almost certainly be greeted with stiff resistance from franchisees.

The franchise agreement is written so franchisors have all the cards. Franchisees know they can’t win a direct assault, so they first will band together and form an “advisory council,” sometimes meaning “a franchisee street gang.” They will engage franchisors head on and continue a productive dialogue as long as their issues are heard and acted upon. If that doesn’t work, franchisees will become passive-aggressive and engage in hit-and-run mischief. For instance, they will spread negative validation, blowing up the franchisor’s already declining pipeline. They stop attending national conferences. They decline assistance from field operations, or worse, enroll field ops teams in their issues, turning them against the franchisor.

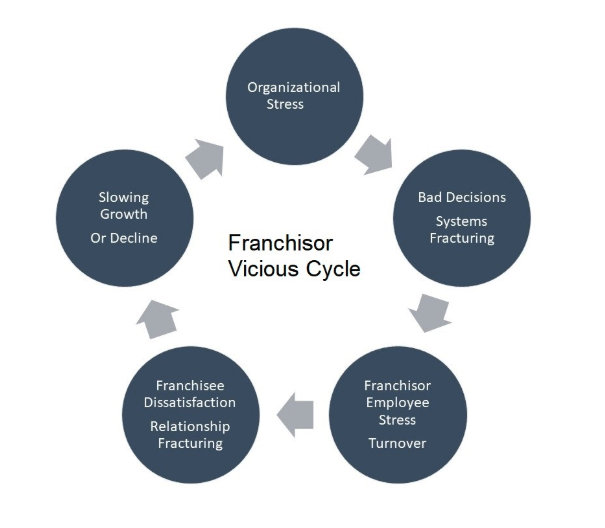

Brand strategy goes out the window as franchisors leaders and employees spin their wheels in a never-ending stream of one-off problems. The brand enters a negative, self-perpetuating, vicious cycle, ultimately becoming the next turnaround brand.

Brand Negative Spiral

Key Culture Shift Inflection Points

The key inflection points regarding culture shift appear to be Early Stage and Emerging Growth, as the chain hits the tipping point and grows exponentially. As we study what happens in franchising, once a chain successfully shifts into an Empowerment and Achievement culture, where franchisees are trained, supported, and equipped to compete in their respective markets, there are no additional cultural barriers to growth unless the chain is acquired by private equity or absorbed into another brand. The acquiring group will bring its own culture and often underestimates what it takes to acclimate a new brand, often creating a 2- or 3-year window of brand bumps and bruises until franchisees and the acquirer figure each other out.

When a company acquires a brand, it typically will break in one of two directions. First, it will establish a sales and growth culture and make big moves to pump up numbers. Or it may break the other way and penny-pinch to aggressively pay down long-term debt or kick up fat bonuses to leadership. Since many franchisors’ boost revenues by driving royalties and acquiring franchisees, franchisees can get squeezed in the process, creating some franchisee consternation and pushback.

Keep in mind these negative cycles occur when the brand is growing and leadership is confident they are making the right moves. These seeds of this cycle are sown while the brand appears to be winning. The cycle may take two or three years to develop and may be difficult to tie back to decisions made at the time. Meanwhile the brand becomes a turnaround situation.

Does your brand need expert guidance?

Leadership of Franchise Performance Group possess over 100 years of experience working with high-value, high-growth franchisors. Clients include Marco’s Pizza, BP, Bright Star, School of Rock, and other national brands.

Complete the form in the footer of this page to start a conversation.