Why Franchising May Soon Experience a Massive Correction

By Joe Mathews, CEO Franchise Performance Group (FPG)

Recently, I was invited to sit down with a number of highly experienced franchise development executives to discuss the current state of franchising. They averaged over 25 years of experience each. Counting my 32 years, the group had a combined 250 years in franchising. Before I joined them, the group had already come to the conclusion that franchising is changing and finding new franchisees is harder than it has ever been. The dialogue started with, “We know a disruption is coming. But what will it look like, where will it come from, and what will be the impact?”

This article attempts to address these questions.

After spending the last 12 months discussing the current state of franchising with private equity firms and thought leaders in franchising and other industries, one thing became clear: We should all be extremely concerned.

Franchising is showing all the telltale signs of a market correction.

Rather than jumping right into our current indicators along with opportunities to transform franchising, we want to lend some historical context to our current set of issues and problems.

We are Entering Into a New Era of Franchising

Franchising appears be be broken into three distinct eras. The third era is about to begin. We will look at the first two eras and then make some predictions about the third.

The First Era of Franchising: Franchising as a Distribution Model (1960-1990)

Ray Kroc (McDonald’s), Fred DeLuca (Subway), Bill Rosenberg (Dunkin’ Donuts), and other Founding Fathers of Franchising largely saw franchising as a distribution model. Having been hired by Fred DeLuca when Subway was just at 400 units, I remember him telling me, “I could have owned them or franchised them. I chose franchising.” Early adopters like DeLuca elected to use franchising as a strategy to eliminate operational complexity, provide expansion capital, and accelerate speed to market. Plus, it looked easier.

For instance, after its first 10 years in business, Subway had only about 12 restaurants that DeLuca and his partner jointly owned. Far short of their 10-year total unit goal, they decided to get into franchising. I joined Subway just prior to their 20th anniversary. That was the year they opened their 400th restaurant. Within the next several years they hit a tipping point and opened thousands. At the time, franchising was thought of as a centralized model. The franchisor would have said, “It’s my brand, my system, my product and services, and (ultimately) my customer.” Franchisees, under the supervision and control of the franchisor, had the rights to distribute whatever products or services the franchisor offered. Franchisors thought of themselves as above the franchisee on the organizational chart. It might have looked something like this:

The franchisor stood at the top of the pyramid, defining the brand and controlling how they wanted the brand represented and customers served. Franchisors thought of franchisees as the low man on the totem pole. Of course, when franchisees originally invested in a franchise, they didn’t come in under the assumption that they were merely a point of distribution subject to the dictates of the franchisor. They came in expecting to be treated like an owner, entrepreneur, and stakeholder, not a pay-for-play manager. This misalignment created tension, and out of this tension came such things as the UFOC (now called the FDD) and the International Franchise Association (IFA).

In my career I’ve talked to hundreds of franchisor executives over the years. I always ask them the following question, “Did you get into franchising by accident or by design?” I can only recall two people saying, “I knew what franchising was and I chose it as a career path.” Most of us franchising lifers tripped into franchising by accident, fell in love with the complexity, the personal relationships, and the challenges, and stayed with it for the long haul. We discovered franchising was far more complex than the binary model of, “Do I own them or franchise them?” We believed franchising was a business unto itself. We found ourselves asking, “But what kind of business? What makes franchising work?”

The Second Era of Franchising: Franchising as a Business Unto Itself (1990-Now)

My generation of franchising leaders discovered the binary “own them or franchise them” question was far too simplistic a way to define franchising. We saw franchising had its own set of best practices, independent of the retail or service sector where the franchisor competed. We saw franchising as a second business, meaning every franchisor was now in two interdependent businesses. The first was the business of selling their product or service. The second was the business of franchising. We saw the franchisor graveyard littered with the bones of potentially great business models and iconic brands that failed not because of their consumer value proposition, but because they never understood how franchising worked. We discovered franchising was its own specialization, transcending the product or service offered or industry served.

But where can one go to learn about and eventually master franchising?

If I wanted to become a lawyer, I would go to law school, where I could find curriculum, professors, libraries, journals, case precedents, commonly understood definitions and language, and scholars dedicated to furthering the law. Almost every specialization known to man has a set of best practices and standards, a curriculum, a certification program, a common vocabulary, and some physical place I can go to learn it.

Except franchising.

Franchising has no physicality. Franchising exists as an amalgamation of IFA conference PowerPoint decks, coffee shop discussions, Certified Franchise Executive (CFE) class handouts, blogs and articles, and conversations over beers at the hotel bar.

Many of these opinions are harmful and subtractive. In my 32 years in franchising, I have heard all of the following taught from a podium by people calling themselves franchising experts and purporting to be offering up franchising best practices:

“If you want to close a deal, tell a franchise candidate you have other franchisees looking at the same territory. Then quickly advertise in that market so you can’t be accused of lying.”

“Sell a franchise to anyone who has the money to buy. Give everyone their God-given right to fail.”

“You don’t need a proven model to franchise. Just sell a few to see if you can. Then design the model after you sell it. Which is smarter: 1. To plan a party and buy all the food and supplies and then send out invitations or 2. To invite people to a party and see who comes, then charge admission, and then buy the party supplies with their money?”

While franchising is a specialization, it’s not yet looked at as an industry. This is why most franchisors can’t tell you how many franchise buyers exist in the marketplace. They often don’t look at the value proposition of their franchise relative to the franchise buyer’s other choices. It is often reported that franchisees fall behind the development schedule of the vast majority of franchise development agreements. Are the franchise recruiters held accountable for consistently structuring unattainable development plans that bury franchisees and stymie the brand? Do they have the skills and experience to create workable market development plans consistent with both the brand’s and the franchisees’ development goals? Can they accurately assess franchisees’ skills and abilities, and the brand’s organizational structure along with its relationship to franchisees’ growth objectives? Or are they just jamming deals through, collecting checks, maximizing commissions, and putting it on the franchisees to figure it out?

On the operations side, how much time does a franchisor spend thinking and talking about battling for market share compared to the time it spends battling franchisees?

Perhaps franchising is a specialization, and, on balance, maybe we aren’t very good at it.

The Current State of Franchising

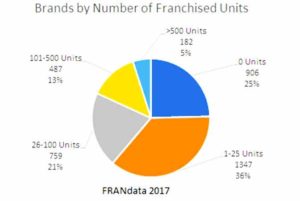

Research firm FRANdata estimates there are approximately 3,800 franchised brands in the United States. FRANdata and FPG estimate that only 15,000 new franchisees enter franchising each year. In any given year, franchise industry reports show 250 to 350 concepts become franchisors. Bottom line, today there is about one franchise brand for every four new franchisees.

If you buy into the premise that investors don’t want the business, they want the results, every potential outcome an investor wants to achieve is probably already available with multiple existing franchisor options. Put another way, we believe franchising is oversaturated and that there are not enough franchise investors to financially sustain the current stable of franchisors.

FPG franchisor models show that most franchisors need 40-100 franchisees/units/operating territories to achieve the financial milestone called royalty self-sufficiency, meaning a franchisor can exist on royalty collections alone without relying on franchise fee revenue to keep the lights on.

FRANdata estimates that more than 82% of brands have less than 100 units or territories. If that’s the case, then four out of five brands struggle to maintain economic stability. Anyone who has ever worked in an unstable environment knows that’s when strategy and long-term planning go out the window.

Is Franchising Creating Its Own Problems or Solving Them?

Based solely on the numbers, one can make the case that even if a franchisor attends events, listens to speakers, reads franchising publications, listens to consultants, follows the prevailing franchising wisdom, and implements best practices, almost certainly the franchisor will stall out before it operates in 100 units or territories.

Perhaps, taken as a whole, the prevailing wisdom is simply a recipe for survival. Perhaps the recipe for success lies outside the current “group think.”

What Does It Really Cost to Franchise?

FPG interviewed a group of franchisors who achieved royalty self-sufficiency. Each franchisor invested an average of $1 million to $2 million to build the necessary infrastructure to support the 40-100 franchisees it took them to achieve their level of royalty self-sufficiency. They found that franchise fee revenue was largely consumed by the franchise development department in advertising and overhead and contributed little to the $1 million to $2 million they needed to reinvest in infrastructure. Royalty revenue from the ramping franchisees eventually built to sustainable levels, but the franchisor had to front $1 million to $2 million before royalties caught up.

A Question to CEOs, Founders and Private Equity Firms Who Made an Investment in Franchising

If you knew in advance that franchising took $1 million to $2 million in investment and more than 10 years to sustain itself, would you still do it? If you knew there were almost 4,000 companies competing for the same 15,000 investors you’re counting on to grow your brand, would you still do it?

Franchisee and Franchisor Misalignment

A typical franchisor requires a royalty of 5% to 8% of franchisees’ sales. On top of that, a typical franchisor charges a 1% or more marketing fee, which a typical franchisor uses to cover the overhead of their marketing department and not towards marketing dollars to generate customers.

A typical franchisee generates 13% to 20% of EBITDA. Put another way, in a mature business, franchisors capture roughly a third and franchisees two-thirds of the available cash flow. And franchisors get paid first, while franchisees bear the entire risk.

At last year’s IFA conference, franchising was touted as the most successful apprenticeship model in the history of the world. Let’s assume for a second the speaker was correct about franchising being an apprenticeship model.

Assume you were looking for a career change and you were presented with the following economic proposition: Pay me $50,000 and I will teach you my business. Then we start a new business together. You put up 100% of the startup costs, guarantee leases, and provide the working capital while I invest no additional capital and assume no additional risk. Then you will pay me one-third of everything you earn for the next 20 years, and no matter what happens, you have to pay me first. My end is guaranteed. In return I will offer you some consulting, coaching, marketing, and training. If you decide to sell your share, I can negate the transaction if the new owner doesn’t honor our current agreement over the next 20 years.

Would you do it?

Franchising as an Inefficient Marketplace

According to the FranConnect/IFA Franchise Sales Index of almost 6,000 franchise sales transactions, out of every 100 inquiries, roughly one franchise candidate makes an investment (1.2% lead-to-close ratio). Surely, all the time, money, and energy franchisors invest in franchisee recruitment could be more efficient. In over 30 years of franchising, this metric hasn’t changed. Finding franchisees is a finding-a-needle-in-a-haystack undertaking.

Entrepreneurship is at a 40-Year Low

According to 2014 U.S. Census data released in September 2016, entrepreneurs launched 452,835 business startups. That’s below the typical 500,000-600,000 new company startups from the late ‘70s through today. If the new franchisee estimates we presented are correct, new franchisees represent only about 3% of new business starts.

The pool of available candidates may be smaller in 2017 than in the previous several years. As many as 1,000 new franchisors entered the marketplace over the last five years, all vying for their perceived share of what is more than likely a shrinking pie.

Perhaps franchising suffers from low awareness, and more people would invest if they were more educated about franchising. We certainly see evidence of that. FPG has been discussing franchising with major private equity firms who were previously unaware of the magnitude of franchising and now see it as an industry hiding in plain sight. We’ve talked to professors and contributors to leading entrepreneurship programs only to hear that franchising is ignored or barely given lip service.

In 2016, the FranConnect/IFA franchise sales index tracked about 500,000 leads, resulting in less than 6,000 deals. If there are 15,000 new franchisees in a given year, and for every new franchisee there are about 100 inquiries, that translates into 1.5 million inquiries as a whole, including the approximate 500,000 inquiries FranConnect/IFA sales index tracked and validated.

While franchising may suffer from an awareness problem, the numbers seem to minimize the impact. More than likely the real culprit is too many franchisors offer too little value to franchise candidates to inspire them to invest.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2014 the unemployment rate dropped from 6.7% in Q1 to 5.6% at the end of Q4. That seems to explain the 2014 decline in small business starts. The unemployment rate as of June 2017 dropped to 4.4%. Traditionally, in a high-unemployment economy, many first-time entrepreneurs view starting a business as a move towards security and they see entering the job market as risky. In a full-employment economy, this dynamic seems to shift. Starting a business appears more risky, and finding a job seems more secure. Many franchisors appeal to first-time business owners. More than likely, their total available market is still shrinking, yet supply continues to grow.

What Happens When Supply is Greater Than Demand?

Prices decrease. But this isn’t happening in franchising. Are royalties declining? Ten years ago, franchisors routinely charged franchise fees of $25,000. Today, franchise fees are closer to $50,000.

The cost of acquiring a franchisee is increasing. Broker fees, for instance, have increased from $8,000 in 2001 to about $25,000 today. Franchisors have responded to these increasing franchisee acquisition costs by raising franchise fees to cover it. Does this reflect the current economic reality?

A typical franchisee recruiter makes a salary of about $60,000 to $75,000 and makes another 50% to 100% on commissions. Yet Franchise Update consistently reports up to 50% of franchise leads are not followed up. FPG has mystery shopped recruiters for 14 years. Our mystery shopper franchise buyers have not once been effectively interviewed beyond self-serving screening questions like, “Do you have the money?” Where else can mediocre performers make over $100,000 per year, jump ship every three years, and still be guaranteed a job?

In many ways the franchise market doesn’t make sense and operates in a counterintuitive manner.

I remember reading an article in the summer of 2008 in which the author showed that the average family in California needed to increase its annual income by over $100,000 per year to support the average mortgage by traditional measures. I remember thinking, “This doesn’t make sense! How is this sustainable?” In September, the market collapsed.

Seemingly, right before any market collapse, the market defies logic.

Finding a Worthy Franchisor is Like Finding a Needle in a Haystack

If FPG models are correct, it takes 40 to 100 franchisees in order for a franchisor to sustain itself on recurring revenue collections. Assume FRANdata numbers are correct and 82% of franchisors are currently operating below 100 units. Further assume the data presented at a recent franchising conference was also correct, and less than 5% of franchise brands pass 100 units within 10 years. If you are a private equity owner of a franchisor, how does this timeline impact your decision-making?

Now Here’s a Scary Thought

Assume again that there are almost 4,000 franchisors fighting for the attention of 15,000 potential investors. What if every franchise candidate was suddenly instructed not to invest in any franchise with less than 40 to 100 franchisees to mitigate their risk of investing in a failing or cash-strapped franchisor?

In the age of information, how long will it be before franchise candidates learn how to successfully evaluate the financial health, risk, uniqueness, necessity, value add and long-term sustainability of a franchisor?

If such a franchisor evaluation model existed, how many franchisors would measure up?

Today, the franchise marketplace is supported by a franchise-buying public largely uninformed about how to evaluate a franchisor’s likelihood of success.

According to IFA’s 2016 Economic Impact of Franchised Businesses, franchising represents $674 billion in sales. Let me ask you a question: How many inefficient, confused, and uninformed $600 billion industries are there? How many $600 billion industries lack trusted industry analysts?

Sophisticated private equity firms and national banks are pouring hundreds of millions of dollars into franchisors and franchisees. Don’t you think they will create models that accurately assess risk?

What will happen when lenders, private equity, and franchise candidates all possess this information? Up to this point, franchise buyers appear to remain in the dark. Given both the size of the industry and the magnitude of risk for franchisees, lenders, venture capitalists, and private equity firms, isn’t it likely a trusted source of information with accurate predictive models will soon emerge? And when they do, given the available data, what story will they tell?

Here is a Scarier Thought

What will happen when franchisees discover right now they are far more scarce and thus more valuable to the franchisor than franchisors are to them?

Here is the Scariest Thought

If you believe that for both franchise candidates and franchisors, finding a fit is like finding a needle in a haystack, answer the following question: What is the quickest and easiest way to find the needle?

First, burn the haystack. Then needles are easier to find.

The Third Era of Franchising: Educated Franchise Candidates, Franchisors, Lenders, and Private Equity Firms Burn the Haystack

The next wave of smart franchisors will predictably reinvent the current franchise model to keep what works, jettison what doesn’t, and ultimately provide greater alignment between the franchisor and franchisee. This means both collaborative decision-making and sharing the rewards in a way that aligns with what each party risks and the value each party brings to the other, the brand, and to the customer.

For example, take the possibility of a $15-per-hour minimum wage. This potential threat increases a franchisee’s risk of doing business by predictably driving the cost of wages at a rate that many franchisees believe can only partially be passed on to the consumer. This decreases franchisees’ profit margins, raises their break-even point, predictably elongates their timeframe to break-even, and decreases the value of franchisees’ businesses.

However, some of this cost can be passed to the consumer, incrementally raising franchisees’ revenues. Since franchisors’ royalty streams are tied to revenues and not to operating margins, in the short run franchisors benefit by increasing the minimum wage. While these new economic realities may make it harder to recruit new franchisees, they will certainly make more money from existing franchisees who are forced to raise prices. That is one obvious area where franchisors and franchisees are not in alignment.

If, like FPG, you believe the long-term viability of any brand is ultimately tied to the predictability and strength of franchisee unit-level economics and the quality of the franchisee-franchisor relationships, then it is conceivable future models will need to capture, balance, and leverage more of both.

In the aftermath of a disruption, franchisees will more than likely capture more economic value and organizational political capital than they currently possess. Perhaps franchisors will share more of franchisees’ risk. Perhaps franchisees will have greater input into problem-solving and decision-making that impacts brand strategy and unit-level economics, eliminating self-inflicted franchisee-franchisor tension.

Franchising 3.0 will need to be robust enough from the franchisee’s perspective to capture the attention and investment dollars of the 450,000-600,000 entrepreneurs each year who aren’t currently choosing franchising, creating more economic stability and brand equity for franchisors.

In Summary: Struggle to Survive or Reinvent and Thrive

As you can see, the current crop of 3,800 franchisors can barely survive with the tiny pool of 15,000 or so investors who open new franchises. Since approximately 18% of franchisors grow beyond 100 units, the market appears to be sustaining less than 700 brands. Many of these are legacy brands with more than 20 years of history. These chains grew in a far less complex and competitive environment. Your chain is facing far more competitive threats today than in previous franchising history.

And where is the help coming from? The current group-think and best practices seem to be a recipe for growing a franchisor to 100 units or less and then stalling out, the evidence being that’s where 82% of franchisors are.

Franchising needs to find new ways or invent new business models or economic propositions which attract the 450,000-600,000 entrepreneurs who start new businesses but don’t yet see franchising as meeting their needs. When an entire industry only captures 3% of the available market, the industry has to look in the mirror and ask, “Why?”

Joining the 5%

According to FRANdata, only 182 brands, representing 5% of current franchised brands, surpass the 500-unit mark. If you wish to build a sustainable national brand of 500+ units, here is what needs to happen:

- If you aren’t already growing at a rate of 25 new units or franchisees per year and don’t already have 200 or more franchisees or units operating, your chain is planted firmly in the 82% of franchisors FPG would classify in the high-risk category. Chances are the market has already declared your investment opportunity as low-value or too risky. That doesn’t mean the problem is not solvable. However, we are saying that statistically the market is discounting your brand, threatening its existence.

- If you are nearing, or just over, the 40-100 unit royalty self-sufficiency zone, don’t get complacent. How you got there is more important than if you get there. A sustainable franchise brand is built one franchisee financial success story at a time. You may have had some initial success selling franchises, which drove your numbers. If unit-level economics don’t improve as you scale, your chain will run into problems. For instance, a franchisor once celebrated their ability to sell 100 franchises over a two-year period. However, their marketing program was unrefined, yielding unpredictable and often unsatisfactory results. The franchisor never flagged their customer acquisition strategy as an issue and sold franchises as fast as they could. This resulted in the franchisor spreading their problems faster than they had the capacity to fix them. They shuttered 80% of their units. They failed to realize that franchising is ultimately a two-metric business: Unit-level economics and franchisee-franchisor relationships. They had a great idea, but a flawed model. They came out too early and too fast, and killed the golden goose. Selling a flawed model is like telling the market, “The bad news is we have cancer, but the good news is it’s spreading.”When done right, at 40-100 units, smart and talented franchisee investors come in greater numbers, creating a franchisee recruitment tipping point. Pioneers and passion players seem to join brands early. Experienced investors (especially those with the capability to be multi-unit owners) tend to join when the model proves itself as both a business model and as a franchisor (remember, franchising is two businesses). If your franchisees are unhappy, your validation is weak, and these smart, talented, and well-capitalized investors will find another brand. Fix any lingering human resources, support, leadership, or franchisee profitability problems now to make sure your validation is solid. Otherwise, you’ll burn through solid candidates and your growth will stall out.

- If you don’t have a balance sheet with $1 million to $2 million cash, you are probably undercapitalized. Just like franchisors who don’t wish to sign an undercapitalized franchisee, franchise candidates don’t stand in line to invest in undercapitalized franchisors. You need to improve your capital position in order to invest in such things as more skilled and experienced infrastructure, tools which improve customers’ brand experience, and resources that drive franchisees’ unit-level economics.

- Hire or buy franchising experience. With the current and future state of franchising, going it alone is not a viable strategy. On one hand, franchisors tell franchise candidates, “Don’t go it alone. Invest in our experience.” But as franchisors, they go it alone and don’t invest in experience. Strategic partnerships and vendor relationships with domain area experts will become more important. Being a brilliant unit-level operator is not enough. Franchisors need to be brilliant franchisors. Don’t confuse years of experience with competency. Hire executives or consultants who already successfully grew brands from 100 units/franchisees to over 500 on their watch and who can bring with them important relationships, tactics, resources, and systems.

In the end, the market of available franchise candidates will always reward polished, skilled, and well-capitalized franchisors who adhere to strict business fundamentals and whose opportunities possess the following attributes:

- The business is unique. Your model is not a copycat, clone, or rip-off of the market leader.

- Defensible. Your business must be difficult to copy, clone, or rip off.

- Profitable. The model must meet the financial needs of its franchisee investor profiles with a high degree of predictability.

- Necessary to the customer. New customers must place a high value on the product or service and existing customers should experience a high risk for change.

- Sustainable for the long haul. Your product or service isn’t a flash-in-the-pan trend. The model is designed for long-term stability, creating the possibility of multi-generational wealth and predictable long-term recurring revenue streams.

- Scalable. Your brand must make the necessary upfront investments to look, feel, and perform like a mature national brand while still in the emerging growth stage.

- Mastery of franchising. You must know the unique challenges franchisors face at the different inflection points during the startup, emerging, regional, and national franchisor lifecycle stages and make the correct business decisions for each stage.

In future articles, we will spotlight how smart franchisors can outflank their competitors by creating more robust economic models and market to exclusive pools of franchise candidates other franchisors ignore.

About Joe Mathews, CEO of FPG

Founder of Franchise Performance Group, Joe Mathews has more than 30 years of experience with such national chains as Subway, Blimpie, MotoPhoto and Entrepreneur’s Source. Joe specializes in franchisor brand strategy and franchisee recruitment. He is a regular presenter at IFA conferences, and has served as an instructor with the ICFE (Institute of Certified Franchise Executives) and IFA Supplier Board. Mathews is author/co-author of four books on franchising, Street Smart Franchising with Don Debolt and Deb Percival, Franchise Sales Tipping Point, Developing Peak Performing Franchisees and How to Create a Franchise Sales Breakthrough. Guaranteed.

Special thanks to Don Welsh, President and Partner, Franchise Performance Group and the smart and capable folks at FRANdata.

About FPG

Franchise Performance Group (FPG) is a franchising specialty management consulting firm offering brands strategic advisory services, relationships, and a full range of tactical services to help franchisors create a chain of 400 units or more. We possess the skilled executives, relationships, and intellectual property to help brands grow nationally and become iconic.

FPG executives have over 100 years of executive franchising experience and have worked with such breakthrough brands as Subway, Sonic, Sylvan Learning Centers, Marco’s Pizza, Arby’s, Great Clips, Sport Clips, BrightStar Care, and Menchie’s.